Spitfire Squadron Organisation and Training

Squadron Organisation

This excerpt on Australian Spitfire pilot training is taken from Australian War Memorial Records AWM173 7/4 Part 2 ‘Narrative of RAAF in Single Engined Squadrons of Fighter Command.’

In single engine fighter squadrons (Spitfire and Hurricane) the normal compliment of operational aircraft is sixteen held on initial issue and at least two or three aircraft held on immediate reserve. These aircraft are manned by about 25 pilots who are divided into two flights, A and B of approximately equal strength. The ground crew are similarly divided and service the aircraft allotted to their particular flight. In actual practice it is usual for each ground crew to have one particular aircraft as their charge. Each of the flights is commanded by a pilot of the rank of Flight Lieutenant and the Squadron is commanded by a pilot of the rank Squadron Leader.

An important man on any operational squadron is the Intelligence Officer. His work consists in seeing that all information which will be of use to the pilots in not only available to them but is actually brought to their notice. He has his Headquarters in the Intelligence Room which is usually established as close as possible to both flights. Such tasks as training in aircraft recognition, supplying the latest information concerning anti-aircraft defences both enemy and friendly, the latest information concerning the performances, armament and tactics of enemy fighters, the interrogation of the pilots after combat – to mention only a few of his many activities – clearly demonstrates the important part an efficient Intelligence Officer can play in a squadron’s work.

When William Brambleberry met and joined 453 SQN, the Intelligence Officer at the time was Flight Sergeant Gordon Henry “Catch” Catchpole of Guildford, Western Australia.

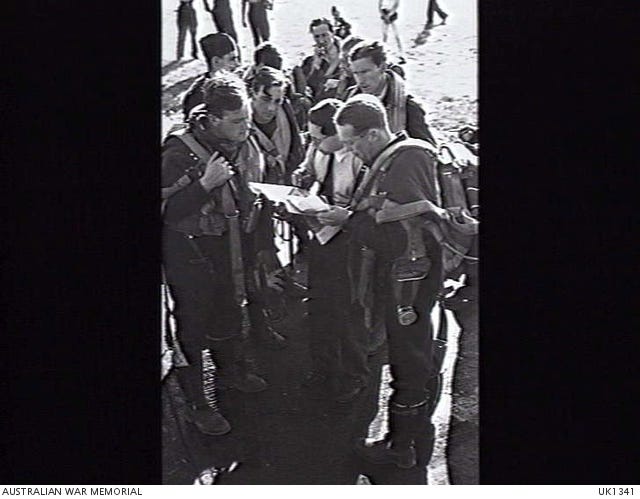

453 SQN Fitters Working on Aircraft

Intelligence Debrief

Squadron Missions

Several different types of missions were commonly flown by 453 Squadron pilots. Their code names were:

Circus – daytime bomber attacks with fighter escorts against short range targets, to occupy enemy fighters and keep them in the area concerned

Ramrod – short range bomber attacks to destroy ground targets, similar to Circus attacks

Rhubarb – fighter or fighter-bomber sections, at times of low cloud and poor visibility, crossing the English Channel and then dropping below cloud level to search for opportunity targets such as railway locomotives and rolling stock, aircraft on the ground, enemy troops, and vehicles on roads

Rodeo – fighter sweeps over enemy territory

Rover – armed reconnaissance flights with attacks on opportunity targets

Scramble – fast take-off and climb to intercept enemy aircraft

Take Off on Sortie

Pilot Training

This excerpt on Australian Spitfire pilot training is taken from Australian War Memorial Records AWM173 7/4 Part 2 ‘Narrative of RAAF in Single Engined Squadrons of Fighter Command.

The first step in the training of all aircrew is the Initial Training School. Here they are given a basic theoretical training and finally categorised as suitable for pilot, navigator, air gunner etc. Those selected as pilots then proceed to an Elementary Training School where they are taught to fly an aircraft such as the “Moth” and where some idea of their ability as pilots is obtained.

At the conclusion of this course those selected as Single Engine Fighter Pilots are transferred to a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they are given a course on single engined aircraft of the monoplane type such as the Wirraway or the Master whose performance and characteristics are approaching those of operational aircraft.

This course is fairly extensive and includes such items as air gunnery and navigation. On arrival in the United Kingdom these pilots are given what amounts to a refresher course at an A.F.U where the same type of aircraft are flown as at an SFTS and finally to a Fighter Operational Training Unit where they are taught to fly the type of machine, e.g. Spitfire or Hurricanes, which they will actually be using operations. They are posted to squadrons as operational pilots.

On arriving at their squadrons however they find that their training is by no means complete from the squadron point of view and that a quite extensive training programme still lies ahead of them. Besides an intensification of their ground training dealing with such matters as aircraft recognition, anti-aircraft defences etc., matters which fall into the province of the Intelligence Officer, considerable flying training is still necessary. At this stage, although the pilot has now quite a respectable total of flying hours in his log book comparatively few of them are in the operational aircraft he will now be flying. Further experience on this aircraft is consequently needed.

In addition, since team work is an extremely important factor in air combat he must be fitted into the squadron’s combat structure and must learn to operate as part of a unit and not entirely as an individual. To obtain these results a considerable amount of flying is necessary. He must fly both by himself and in squadron formations of all kinds from the pair which forms the basic combat unit to the full squadron formation. Also since ground control is a major factor in fighter operations he must gain experience of its working before being allowed to take part in operations.

All this training is organised into the normal squadron routine, but it will be readily appreciated what a large commitment a newly formed squadron has in this respect and that several months may elapse before a squadron can be regarded as fit for operations.